With newly-announced Pink Floyd box set The Later Years set to arrive in November, we spoke to the band's creative director Aubrey 'Po' Powell about his work with the band...

As one of the co-founders of Hipgnosis, the art and design team behind some of the most iconic album covers ever made, Aubrey 'Po' Powell has worked with a long list of legendary artists from Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath to The Police and XTC. But along with his former partner Storm Thorgerson, Powell's work is most often associated with Pink Floyd, for whom Hipgnosis designed a series of album covers over a period of around 15 years, including the iconic light prism featured on their seminal 1973 album Dark Side of the Moon.

Powell left Hipgnosis in the early 1980s to focus on creating music videos for the likes of Robert Plant during the rise of MTV, but Thorgerson continued to work with the band until his death in 2013. After that, Powell reconnected with his old friends in the band to work as creative director on a series of projects, including the Pink Floyd exhibition Their Mortal Remains, which premiered at London's Victoria & Albert Museum in 2017.

More recently, Powell has been overseeing the newly-announced Pink Floyd box set The Later Years, which follows the 2016 box set The Early Years and focusses on the post-Roger Waters years, during which time the band released The Division Bell and the resulting live album Pulse.

Announced last week, The Later Years contains a host of previously unreleased material that Powell uncovered while working on the exhibition, compiling all the best bits for inclusion in the box set and uncovering a few surprises along the way.

The album is set to arrive in November and is available to pre-order in our online store. Ahead of the announcement we caught up with Powell for a chat about his work for Pink Floyd over the years and how the new box set came together...

If we can briefly go back to the beginning of your association with Pink Floyd, you knew those guys before they were in a band together didn't you? Did that friendship pre-date Hipgnosis as well?

“Well, it kind of started because I was at school near Cambridge and Roger (Waters), Syd Barrett and David Gilmour are all from Cambridge. We all used to play cricket against each other, or football, or rugby or whatever. Relationships formed and Cambridge became a sort of hotbed of what I would consider at the time a rather sort of bohemian scene. Many of the guys I just mentioned played in different bands and we all hung out together, and we all went to London round about the same time, about '65 or 66 I think."

“Syd went to Camberwell school of art, Roger went to architectural college, where he met Nick Mason, so those friendships sort of formed and Storm and I shared a flat in South Kensington, he was at the Royal College of Art and I was at the BBC. Then Pink Floyd started and of course because we were all friends we all used to go to the early gigs and hang out together."

Was that how they ended up being your first commission?

“One day, when they were looking for an album cover for the second album Saucerful of Secrets, we were all in a room together and they were saying: 'Well, what are we going to do? We don't want to follow the normal route that everybody else goes down with a photograph of the band on the front cover', which in those days record companies pretty much insisted on. I remember Storm putting his hand up and saying 'Why don't you give us a chance?'. And we weren't even Hipgnosis by that point, we were just two guys doing book covers and taking photographs, just to earn a living, you know? We were all very poor. And they said 'OK, go ahead'."

“I was very good in a dark room and Storm had plenty of ideas, and together that sort of fell into place somehow. And it was very appropriate for Pink Floyd, because they were sort of titled 'the psychedelic space rock band of London', which they hated.”

They did?

“Yeah, I think they did because they didn't want to be labelled in that way, but they got labelled. Roger Waters always had great ambitions to be a pop star, he wanted to be rich, he wanted to be famous. Syd Barret did not. But really it was just circumstance, serendipity. It was right time, right place. And suddenly Storm and I found ourselves being asked to do album covers for other people, which were The Pretty Things, Alexis Korner, Free – a new young band at the time who of course became Bad Company in the end – and we suddenly found ourselves in this world of doing album covers, which was the furthest thing from either of our minds."

"Within a couple of years, we had got a studio in Soho and embarked on a fully-fledged career. We became, I suppose, one of the leading art studios at the forefront of designing album covers. And that ran for 15 years.”

You worked with them all the way through the 60s and 70s, was it just album artwork or were you involved with their other visuals too?

“No, not at all. We simply designed their album covers and embarked on one or two other areas like posters and live photographs, pictures of the band on tour and stuff like that. It all went swimmingly well, and Dark Side of the Moon in 1973 was the absolute highlight of that relationship and has probably become one of the most iconic album covers there has ever been. And it's still used to this day by Pink Floyd as a kind of symbol for themselves."

“But I think the thing is that, although were were always associated with Pink Floyd a lot of the time with what I would call our surrealist work, I have to say that the work we did for Led Zeppelin's Houses of the Holy, or Peter Gabriel or Genesis or Yes, it stands the test of time as much as anything else. Pink Floyd just happened to be a part of that.”

There must be something special about the work you did for Pink Floyd though, considering you'd all been friends for so long?

“The thing that's most important of all, I think, is that the relationship between myself, Storm and Pink Floyd was one of trust and friendship, and it was very jocular, there was a lot of fun in it. Things like Atom Heart Mother, with the picture of the cow. It was just an idea that came out of a meeting, Storm and I jumped in a car and rode to Potter's Bar on the outskirts of London, found a field full of cows, photographed them and brought them back, and there was this wonderful picture of the cow. I remember going into Abbey Road and saying 'what do you think about this?', and Roger saying 'That's it!'"

“We said 'The only thing is, no name on the front cover, and no title.' And everyone went 'Of course', which absolutely incensed the record company and the management, but actually it was just lateral thinking, doing the absolute antithesis of what was expected. I'll always remember walking down Sunset Strip in L.A. and seeing a huge billboard with just the cow on it, and people were wondering what it was. Was it a new movie? A horror film? A new book? Then on the day of the releases, they put 'Pink Floyd, Atom Heart Mother' next to it, and it worked. It generated a lot of publicity and interest, and that's exactly what Pink Floyd were all about. They were enigmatic, they were rarely interviewed, they were rarely seen even during their live shows. They would have their backs to the audience or be hiding in the shadows of these amazing light shows.”

Or building a wall in front of them...

“Yeah, exactly. And so that sort of fitted in with Pink Floyd. And I don't think it was necessarily because of Pink Floyd, it was just the way that Storm and I worked. We always thought differently and wanted to be different, to not conform to what would be considered a normal, commercial album jacket that a record company would love to have. We just weren't interested, we were interested in the art, not in anything else really.”

You've worked with an incredible list of people besides Pink Floyd though, perhaps it was that attitude that appealed to so many of these artists?

“Yes, I think that's what it was. You've got to remember that albums sold in tens of millions, so the industry was awash with money. So as a studio, if we came up with an idea that was outrageous like 'Let's go to Hawaii and photograph a sheep on a couch' – that was for 10CC – it was like 'Oh yeah, why not? Let's do that.' If Paul McCartney goes 'You need to be in New York tomorrow, can you get on a Concorde and sort this out?', it'd be 'Yeah, OK'. It was a period of time when anything was possible. And artists, because of their earning potential with albums, they had creative control and could do what they wanted, basically. And that was so infectious for us, it was a licence to do whatever we wanted."

“It was an incredibly privileged time, I don't think you could do that now in a million years. First of all the budgets aren't there, secondly, visuals have sort of taken a back seat. I mean the CD is disappearing, the retro vinyl has come back, not how it used to be, but it's still an interesting canvas. But the Halcyon days are gone. So there was a period of time, for those 15 years, it was a joy to be around, and a privilege to work for an have the trust of those artists. To have Led Zeppelin or Pink Floyd say 'hey, work with me, let's come up with something interesting together' was just extraordinary, and I take my hat off to all those artists for that.”

You did your last work for Pink Floyd with Hipgnosis in the early 80s – was that motivated by a desire to move into filmmaking and other things? What prompted the change?

“Well, the writing was on the wall. Punk had happened. The industry was in a little bit of dire straits, they'd spent huge amounts of money, and when punk came along everything was done on a shoestring. And I think those indulgences of prog-rock were put to one side, it wasn't considered to be the right thing to do. MTV had started, we wanted to make films so we slipped out of album covers and went into moving pictures. And of course, that was the heyday of music video, which was incredible too. And we took all of our clients with us. It was wonderful. But then Storm and I fell out, very badly, and we parted company.”

So there's a gap of over 30 years before you started getting involved with Pink Floyd again – how did that reconnection come about?

“He went back to doing album covers, carried on with that and working with Pink Floyd, and I didn't. I formed a film company and had great success in that world, until Storm died in 2013. And I hadn't worked with Pink Floyd for a number of years by that point, but I think there was a meeting before he died with Nick Mason and David Gilmour to talk about what was going to happen. Storm said 'Why don't you let Po take over?' And I didn't really want to do it, to be honest.”

Oh, you didn't?

“Not really, I'd got my own career and I felt like I would be going backwards slightly. But I said 'OK, we'll give it a year, see how it pans out'. And it's been six years now, working as their creative director. And boy, have I had a lot of fun doing it. One of the things that really got back into that was that I suggested we do an exhibition of Pink Floyd, which was at the V&A, Their Mortal Remains. I was creative director for that and it was so interesting, it was three years of my life putting it all together and it was hugely successful. And I felt that actually, reconnecting with Pink Floyd like that, I'd done a good job for them and myself. I've enjoyed it, and I'm still enjoying working with them, it's great fun.”

Didn't you get involved for the Division Bell anniversary initially?

“Well, yes, there were various things. And I think the other thing which cemented the deal, in a way, was my relationships with David Gilmour and Roger Waters. I think it's fairly well-known that they don't exactly get along too well, and because I've known them all since I was 15, I somehow was able to go from one to the other and discuss ideas, and help with the diplomacy of trying to reconnect elements of Pink Floyd that could move forward. The exhibition was a perfect example of that, getting the stamp of approval from all three members of Pink Floyd, and without that, it never would have happened. So I've found myself in a position which is constructive as well as being creative. It's worked out rather well for all of us, I guess.”

What has your involvement been with The Later Years box set?

“Total involvement, right from the very beginning. That's my job. We'd previously done a box set called The Early Years. So the idea was to another about the later years, which is primarily albums like A Momentary Lapse of Reason, The Division Bell, the Pulse tours, all that sort of stuff. And there was a lot of previously unreleased material, stuff that's never been heard, rehearsal material, film that's come out nowhere, that nobody's seen before. When you're presented with a menu of stuff and somebody says 'OK, we need to come up with an idea for how exactly this is compiled and put together,' that's exactly what I enjoy most."

“The first thing we needed to do was to find an idea for the album cover. Now, as a creative director, what I like to do is not do everything myself, because I think there are so many other talented people out there with contributions to give. So what I do with Pink Floyd these days, and what I have done since 2013, is go to people that I think are aspiring or interesting and say 'OK, here's a project, come up with an idea.' One of those people was Michael Johnson, of Johnson Banks design studio, and they came up with a whole bunch of interesting propositions.”

Do you then pitch the best of these to the band yourself?

“I showed them to David Gilmour and Nick Mason individually and they both agreed on something, which was the thing I really wanted. It's this landscape with a small child in it and the folding of lamp posts as the child walks down the road. It's slightly sci-fi and otherworldly, and I suppose it's a metaphor for power, which is what Pink Floyd is all about. And I think the symbol of a small child walking into the distance in an extraordinary landscape is also something to do with this idea of the Later Years, because all of us – and I include myself and Pink Floyd in this – we're all in the autumn years of our lives, so it was an important metaphor to make, visually, I think.”

Like a kind of 'riding off into the sunset' sort of thing?

“Well, not exactly, it's called The Later Years but I'm sure David and Nick will carry on. Nick's out there with his band Saucerful of Secrets right now, David's still got plenty of songs under his belt still and I'm sure there will be other things to come along. If you look at The Division Bell, I think it was the biggest-selling album for Pink Floyd since Dark Side of the Moon. When Roger Waters left in 1987 a new Pink Floyd emerged from that, which has been phenomenally successful, so I think it was important to justify that period of time. There have been three sort of eras of Pink Floyd, one with Syd Barrett, one when David Gilmour joined and then the next part with just Nick and David. So I think it was important to celebrate these great albums that David and Nick made together, and that's what we've done with the box set.”

We saw that there is a lot of unreleased audio-visual material in the new box set, can you talk us through some of that?

“Well, one of the things, for example, is the Pulse concert. With technology now we've come to expect the highest quality. I mean, if I film something now I'll shoot it in 8K. Of course, it's amazing how technology has changed in the last 30 years, and since the most recent version of Pink Floyd has been out there, it's changed radically. But when you go back into the archives, which I did recently and looked at everything we could possibly find, you look at a film like Pulse that was released 20 years ago on DVD and probably VHS."

"You go back to the original masters and there's only so much you can do, it was all shot on Beta SP, which is a format I would liken to steam radio. But these days there are ways of manipulation and digital restoration that mean you can bring something up to looking pretty damn good. So that's one thing that I've done and it looks pretty amazing, and of course, because David had all the original master tapes we were able to re-mix the sound. It looks and sounds great.”

What else can we expect from the new box set in terms of visuals?

“I think the most interesting part of the package, for me, was finding 350 film cans which contained the Delicate Sound of Thunder film. What was incredible was that all that film negative was in unbelievably good condition. I digitally restored the whole lot, we up-res'd it to 4K – and in some cases 6K – and previously it had been cobbled together a bit. I realised that Wayne Isham, who was the original director of the film, had shot it all on 35mm and had a terrible job trying to put his film together."

"Pink Floyd are never easy to film at the best of times, because of the nature of the concerts. He'd created this melange of images that were all superimposed onto each other, and I couldn't really work out why he'd done that but then I did, because it basically been shot in quite a ramshackle way. Not deliberately, it was just he nature of how you shot films in those days. There wasn't the sophistication and communication that we have shooting live concerts now.”

So what did you do?

“I took all this film, restored it all and re-edited it. It took 16 months to do it, and we've brought it up to the most incredible two-hour concert of absolutely beautiful film, it looks amazing. David re-did the sound and remixed it all, and the result is just spectacular. And it's the only Pink Floyd concert film, ever, apart from Live at Pompeii. Apart from that, there is no other live film of the whole Pink Floyd band."

"They filmed The Wall, but not successfully, it didn't look very good so they've never released it. There have been individual films of David Gilmour's tours and individual films of Roger's tours, but there's never been a Pink Floyd live film that you could show in a cinema. This looks and sounds amazing, it's beautiful, it's absolutely incredible.”

Are there any plans to do that? Show it in cinemas?

“We've shown it a couple of times in a cinema for ourselves, just to make sure that it works! I think there are plans afoot to screen it, but I don't know, I can't say more than that because nobody's agreed to that as yet, but I'm sure something will come of it.”

What about the other unreleased material you mentioned?

“There are recordings of rehearsals from Division Bell that have never been heard, there's a big picture book with lots of photographs that have never been seen before, as well as drawings and illustrations of some of the stage sets. In a sense, I've been fortunate to have done the exhibition Their Mortal Remains, because out of that I discovered a whole load of stuff looking through the archives that's never been seen before. So it's kind of a culmination of that too, but I think as a box set it really has got something of Pink Floyd that has not been seen before, it's the gathering together of a lot of bits and pieces, and none of it is scraping the barrel, it's all very good quality and really wonderful.”

Sounds like quite the treasure trove...

“That's exactly what it is! You've hit the nail on the head, it's a treasure trove of pieces that I think anyone who is a fan of Pink Floyd will love, but also anybody who is being introduced to Pink Floyd for the first time will find some fascinating pieces in there.”

The Later Years: 1987 - 2019 is available here in our online store.

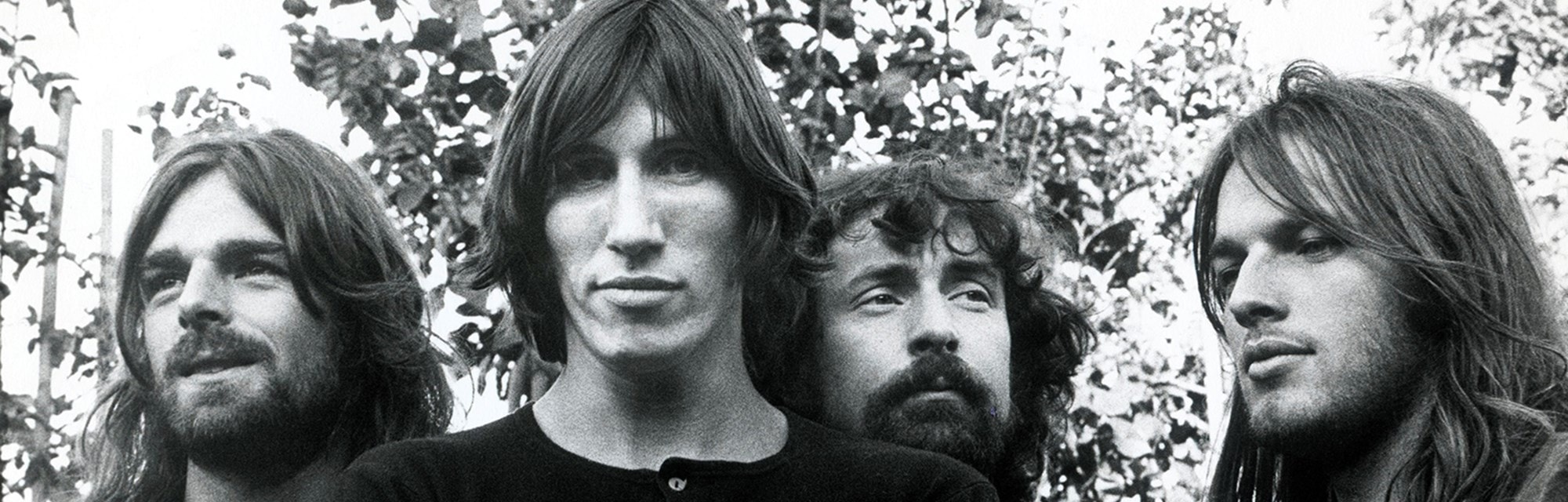

(Image credit: Photography by Dimo Safari, Pink Floyd (1987) Ltd.)